Freya von Moltke, Francis Huessy and Harold M. Stahmer: Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy

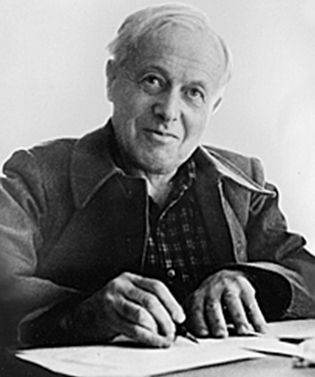

Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (1888-1973)

A Brief Biography

Eugen Rosenstock was born in Berlin on July 6, 1888, the son of Theodor and Paula Rosenstock. Theodor was a banker who had been compelled to enter that profession to support his widowed stepmother and stepsister; if he had been able to choose, he would have pursued a scholarly education. In due course, however, he became a member of the prestigious Berlin Stock Exchange. Paula Rosenstock was the daughter of the head of a well-known Jewish school in Wolfenbüttel. Eugen was the fourth child among six sisters.

After his first years in a school for wealthy families, Eugen Rosenstock transferred to the Joachimsthaler Gymnasium, a school known for its rigorous academic standards, particularly in the classics. Following his father’s wish, Eugen went on from there to study law at the universities of Zürich, Heidelberg, and Berlin. At age 17 he joined the Protestant Church, which did not seem much of a conversion to him because Christian habits had already become a part of family life. Gradually, however, his faith became central for his work. In 1909, at the age of 21, he received a doctorate in law from the University of Heidelberg. Studying history would have been one of his first choices, and philology (language) was his abiding passion from early on. In 1912, he began to teach constitutional law and the history of law at the University of Leipzig, the youngest Privatdozent at the time.

Early in 1914, Rosenstock went to Florence to conduct historical research with his brother-in-law, Ernst Michel, then editor of the German encyclopedia Brockhaus. There, he met a young Swiss woman, Margrit Hüssy, who was studying the history of art in Florence. They married that same year, just before the outbreak of World War I. Drafted at once as a lieutenant in the mounted artillery, he was stationed at or near the Western front throughout the war, including 18 months at Verdun. During this period he organized courses for the troops, replacing the limited instruction in patriotism with broader topics. In 1916, he and his friend, the Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, also on active duty, exchanged letters on Judaism and Christianity. That correspondence has since become well known, and much of it is now contained in Judaism Despite Christianity.

Rosenstock was keenly aware that World War I was an historical watershed. At the end of the war, not wishing to return to teaching at the University of Leipzig, he sought new options better suited to a changed world. Together with a member of the board of Daimler-Benz, the German car maker, he started and edited the first factory newspaper in Germany, the Daimler Werkzeitung. Also, together with Leo Weismantel, Werner Picht, Hans Ehrenberg, Karl Barth, and Viktor von Weizsäcker, he founded the Patmos Verlag, publishing works focused on new religious, philosophical, and social perspectives. A journal, Die Kreatur (1926-30), followed, edited by Josef Wittig, a Roman Catholic; Martin Buber, a Jew; and Viktor von Weizsäcker, a Protestant. Among the contributors were Nicholas Berdyaev, Lev Shestov, Franz Rosenzweig, Ernst Simon, Hugo Bergmann, Rudolf Hallo, and Florens Christian Rang. Each of these men had, between 1910 and 1932, in one way or another, offered an alternative to the idealism, positivism, and historicism that dominated German universities. Rosenstock himself published Die Hochzeit des Krieges und der Revolution (The Marriage of War and Revolution, 1920), a collection of current events essays that were full of prophesies and warnings. Unfortunately, some of these were later to be fulfilled.

In 1921, Margrit and Eugen had a son, Hans. In 1925, they legally changed the name to Rosenstock-Hüssy, but it was not until after Eugen’s emigration to the United States that he used the hyphenated name professionally.

Although never a Marxist, Rosenstock was invited to start and head Die Akademie der Arbeit (Academy of Labor) in Frankfurt/Main in 1921. This institution offered courses and seminars for blue-collar workers, but he resigned in 1923 over differences with the trade union representatives. Nevertheless, he did not give up his involvement with adult education and his efforts to give industrial workers a voice of their own in society.

In 1924, Rosenstock published Angewandte Seelenkunde (Practical Knowledge of the Soul) wherein he outlined for the first time his radically new method for the social sciences based on language, the spoken word, and his “grammatical approach,” which he later called “metanomics.” This method remained at the heart of all his later works and was expanded upon in his two volume Soziologie (1956-1958): Volume I, On the Forces of Common Life (when space governs), and Volume II, On the Forces of History (when the times are obeyed). He further elaborated these ideas in another two-volume book, Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts: Eine Leibhaftige Grammatik in Vier Teilen (The Speech of Mankind: A Personal Grammar in Four Parts, 1963-1964). (Many chapters from these volumes are available in English as Speech and Reality and The Origin of Speech.)

Rosenstock was granted a second doctorate in philosophy from the University of Heidelberg in 1923 for his scholarly medieval study Königshaus und Stämme in Deutschland zwischen 911 und 1250 (The Royal House and the Tribes in Germany between 911 and 1250), which he had written in Leipzig and published in 1914. He then lectured at the Technical University of Darmstadt in the faculty of social science and social history until he was offered a job at the University of Breslau as a full professor of German legal history, a position he held from 1923 until January 30, 1933.

In Breslau, apart from being an inspiring and admired teacher, Rosenstock became active in many other ways. In response to and together with some of his students, he helped organize workcamps for students, farmers, and workers to deal with the atrocious life and labor conditions at coal mines in Waldenburg, Silesia.

When Rosenstock’s friend, the Catholic priest Josef Wittig, was excommunicated and lost his right to teach church history at the University of Breslau, he stood by Wittig and together they published Das Alter der Kirche (The Age of the Church) 1927-1928. That work contained two volumes of essays on the life of the Church and a third volume devoted to a statement about Wittig’s excommunication.

In 1931, Rosenstock wrote and published the first of his major works: Die Europäischen Revolutionen–Volkscharaktere und Staatenbildung (The European Revolutions and the Character of the Nations), one thousand years of European history created in five different European national “revolutions” that collectively came to an end in World War I.

On January 30, 1933, Germany fell to National Socialism, and Rosenstock left Breslau at once. By the end of that year and with the help of C. J. Friedrich, professor of government at Harvard University and the only person Rosenstock knew in the United States, he had been appointed Kuno Francke Lecturer in German Art and Culture at Harvard.

Rosenstock-Huessy frequently mentioned God in class. This grated on the secular beliefs of other Harvard faculty members.Rosenstock also often attacked “pure,” “objective” academic thinking. Profound differences of opinion ensued and led, in 1935, to his accepting an appointment as professor of social philosophy at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. He made his home in nearby Norwich, Vermont. He taught at Dartmouth until his retirement in 1957, inspiring generations of students.

Despite the “falling out” with Harvard, Rosenstock-Huessy had made important friendships there that helped him when he began to write again. His first effort was to rewrite his earlier book on revolutions in English under the title Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man (1938). The Nietzsche scholar, George Allen Morgan, assisted him in the preparation of The Christian Future or the Modern Mind Outrun (1946). Alfred North Whitehead, also at Harvard, was among Rosenstock-Huessy’s admirers.

Rosenstock-Huessy continued his pioneering efforts on behalf of voluntary work service in the United States. At the urging of Eleanor Roosevelt, the journalist Dorothy Thompson, and other prominent figures, President Franklin D. Roosevelt tapped Rosenstock-Huessy to lead the creation of a special Civilian Conservation Corps camp in the woods of Vermont. Involving mainly students from Dartmouth, Radcliffe, and Harvard, its purpose was to train young leaders to expand the seven-year-old CCC from a program for unemployed youth into a work service that would accept volunteers from all walks of life. It was called Camp William James because of that philosopher’s search for a “moral equivalent of war.” It was disbanded when the United States entered World War II. Rosenstock-Huessy’s writings about voluntary work service have often been cited as influential in the design and development of the Peace Corps.

After the war and continuing through his retirement from Dartmouth, Rosenstock-Huessy was a frequent guest professor at many universities in Germany and the United States. He remained active in lecturing and writing until his final years. His output comprises more than 500 essays, articles, and monographs, including 40 books.

His connections to the local community were and always remained strong. In 1959, Margrit Rosenstock-Huessy, died. In 1960, Freya von Moltke, widow of Helmuth James von Moltke, who opposed National Socialism and was executed by the Nazis, came to share Rosenstock-Huessy’s life. Her husband had been a student of Rosenstock’s in Breslau and a participant in the original Silesian workcamps. Rosenstock-Huessy died on February 24, 1973. Rosentock-Huessy’s extraordinary insights continue to touch and inspire the lives of many people from all walks of life.

Prepared by Freya von Moltke, Francis Huessy and Harold M. Stahmer. [Bracketed notes regarding books have been added for Internet links.]

This text was first published on members.valley.net/~transnat/erhbio.html